1/5/09- Son House- Father of the Delta Blues: The Complete 1965 Sessions 2CD

Guru Guru- UFO LP 1970

High Places- self titled CD 2008

Sunny Murray- Big Chief LP 1969

Guru Guru- UFO LP 1970

High Places- self titled CD 2008

Sunny Murray- Big Chief LP 1969

1/6/09- Little Feat- Sailin’ Shoes LP 1972

Linda Perhacs- Parallelograms- LP 1970

Andrew Hill- Andrew!!! LP 1964

1/7/09- The Pogues- Rum Sodomy and the Lash LP 1985

Fred Frith- To Sail, To Sail CD 2008

Miles Davis- The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel 1965 CD Disc One

1/8/09- Animal Collective- Merriweather Post Pavilion CD 2008

Shark Quest- Battle of the Loons CD 1998

Andrew Hill- Andrew!!! LP 1964

1/9/09- Bill Dixon- 17 Musicians in Search of a Sound: Darfur CD 2008

1/10/09- Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers- Three Blind Mice Volume Two CD 1961

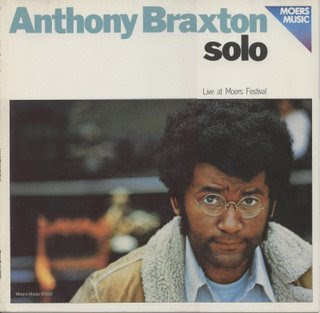

Anthony Braxton- Solo Live at Moers Festival 1974 LP

1/11/09- The Fall- I am Curious Oranj CD 1988

Anthony Braxton- Solo Live at Moers Festival 1974 LP

John Coltrane- One Down One Up: Live at the Half Note 2CD 1965

Cecil Taylor- Stereo Drive LP 1958

Cecil Taylor- Jazz Advance LP 1956

Andrew Hill- Andrew!!! LP 1964

Son House

MONDAY 1/5- Son House, like Mississippi John Hurt and Skip James, was a legendary early bluesman who stuck around long enough to get a nice helping of rediscovery acclaim. And the Columbia Roots ‘N’ Blues two disc collection is sterling documentation of an autumnal artist working through his songbook with the air of summation and satisfaction. Blues hardliners have complained the House’s playing here lacks the fiery sharpness of his indispensable early sides, and it’s true. But. BUT. There is often a but, and here it concerns the music’s clarity and warmth, which really brings out the beauty in the playing and helps to amplify the history and ceremony behind the recordings. And it’s not like they had to prop House up in front of the microphone. His voice is still strong and his playing limber and emotional enough to communicate clearly that he could still conjure up the essence of what made his music such a big deal to folklorists, collectors, and younger musicians. Canned Heat’s Al Wilson plays some backup here, and if that scares you it shouldn’t. He sounds fine, more than just a respectful accompanist while never trying to assert himself beyond the role of support. This is House’s gig, and he does a grand job of showing his stuff. The mix of tough and cutting slide blues and spirituals provides a sustained study in the inner conflict that often surrounded the lives of many blues greats, and when this is combined with House’s undeniable stature in the history of the music, this set acquires a magnitude that’s the equal to the late efforts of Hurt, James, Fred McDowell, Furry Lewis, or Mance Lipscomb. The last observation I’ll make is again concerned with recording technology, specifically how these sessions allowed House to stretch out and capture something closer to the way these songs probably existed in the more natural live setting instead of the truncated nature of the early 78rpm recordings. This is also true of the stuff Alan Lomax documented in the early 40s, but again, the aura of a professional, non-crap studio session really adds some deep flair to the seven minutes of the brilliant “Death Letter”. This whole thing is simply a big fat bumblebee’s golden kneecaps. Anybody who wishes to have their ass kicked by last century’s sounds of survival will most certainly be pleased with its contents.

Guru Guru were part of Germany’s Krautrock scene, and while they don’t have the name recognition of Neu!, Faust, Kraftwerk, or Cluster, they are perpetually bubbling under those groups and exist as an ever ready fix to those who’ve become addicted to the deep sonics of that regional era. The expanse and heaviness on display on their debut recording is quite attractive, and as a piece it fits snugly into the puzzle that was Europe’s ‘70s-era left-field rock excursion. Guru Guru also rub up against jazz in a way that makes them Continental bros-in-arms with bands like Soft Machine and King Crimson while basically sounding almost nothing like them. This is really great stuff that I’m just getting a handle on, so expect more musing at a later date.

My first thought about the full length by High Places was something close to “not as good as the earlier release available through Emusic”. My second listen made me rethink that, somewhat. This record is cleaner, more graspable and comes attached with the undeniable factor of familiarity and the expectations that can’t help but foster. Experiencing it a second time gave me the idea that while my hopes were initially somewhat dashed, they were confounded in a way which will likely lead to other eventual pleasures. I’ll let you know how it turns out.

Anybody who spends time digging in the fertile soil of free jazz history will encounter the name Sunny Murray. Due to longevity and the undeniable importance of many sessions where he left his contribution, he is essentially the key avant-garde drummer of the 1960s. Murray was a member of the Albert Ayler Trio, assorted Cecil Taylor groups, played with Archie Shepp and Dave Burrell, and released some major recordings under his own name. Where many free drummers of the era still held a loose grip on some type of recognizable jazz form, Murray was almost completely abstract in his engagement with his other musicians, and as a result helped to broaden the possibilities for the new music. Big Chief is a fine example of the large group intensity that was being undertaken as the decade closed, and it’s too bad it doesn’t have a larger reputation, for the recording sits quite nicely with the bolder, more uncompromisingly out sessions that were recorded for BYG or ESP at the same time. Murray’s leadership shouldn’t imply that this is a drum focused session, though his playing is outstanding throughout. It’s really a cooperative endeavor with the added attraction of hearing a bunch of under recorded players in fine form: Kenneth Terroade on tenor, South African Ronnie Beer on alto, obscure West Coaster Becky Friend on flute and Francois Tusques on piano are just three examples. Alan Silva had a touch more exposure, playing with both Ayler and Taylor as well as throwing down a wicked ESP release under his own name, but it’s still wonderful to have another session from this much underrated string improviser. Obscure photographer and writer Hart LeRoy Bibbs contributes a fine touch of tough poetics to the group, and a good basic reference point for Big Chief’s sound would be Albert Ayler, particularly on the massive closing piece “This Nearly Was Mine” by Richard Rogers, here transformed into a thick horn lament that recalls more than slightly Ayler’s Impulse! material. I still think Sonny’s Time Now is the best Murray release from the era, but this one is a major statement, loose and tough with an air in insistence about it. Any partisan of free jazz will want to know it.

Sunny Murray

TUESDAY 1/6- Sailin’ Shoes is a grand tour through the deluxe mind of the late Lowell George, a guy who could use a boost or three to his posthumous standing. His career was (at least in its first half) quite varied and interesting, featuring work with both Zappa’s Mothers and killing backup on John Cale’s brilliant Paris 1919 LP, and of course he led Little Feat, who kicked out an initial stream of albums that managed to integrate a bunch of different ingredients (blues, country, mild psych, funky New Orleans) into their sound in a very deft way. George’s integration of varying elements was smart but lacked the sometimes obnoxiously brainy aura of Zappa’s stylistic hodgepodge, plus he was refreshingly brief in an era polluted with blowhards. The debut is probably my favorite, but this record includes the powerful combo punch of the sweet reworking of George’s classic truck driving anthem “Willin’” (the equal to any song in the hippie-country canon, in my estimation) and the scorching bluesy grouchiness of “A Apolitical Blues”, which is possibly the most underrated blues ditty by a white-boy interloper from it’s era. But the whole damn record is a slice of prime junk. George’s slide playing is unique and seductive, his vocals never overstep into wailing minstrelsy (being smart enough to avoid aping his influences), and the total goes down smooth to the perfect degree. It’s true that the band overstayed their welcome, continuing long after George’s early death, and that professing admiration for the Little Feat in public means risking having to suffer the company of Jimmy Buffet fans, but when Sailin’ Shoes plays all that dissolves into nothing. It’s a fine statement from a once fine band, and that will always be welcome.

-

Linda Perhacs is one of the legions of one record wonders to be rediscovered and championed by contemporary artists as a euphoric chapter in the book of lost grails, in the case the freak folk edition, leather bound and reeking of patchouli. Her one record was underground in a way that is different from say Skip Spence’s Oar or Joe Byrd and the Field Hippies’ American Metaphysical Circus. These two were long established cult items, much bandied about before they were eventually given CD reissues and became entrenched as cornerstones of their wide open era. The Perhacs record endured a long period where it seemed to undeservedly sit in the vast sea of recorded ephemera, only being discovered, culted, and reissued with the arrival of the New Weird America/psyche folk movement. Devendra Banhart enthusiasm surely played a big part in this, but most of the credit for the records redemption should sit with Perhacs herself. The gradually creeping oddness in her folky, airy, proudly feminine sound is seductive over the course of the record, and by the time the inspired psyche derailment of the title track arrives, it is clear that the Parallelograms’ neglect was wholly undeserved. The introspective (bordering on melancholy, at times) feel of much of this will be welcome to those who are bugged by maypole frolicking, though methinks that pixies and sprites known to partake in that activity will find this appealing as well. She can also chug acoustically in fine fashion and provide a more popish side that is far more personally preferable to the Carly Simon-ish feel many gals of this era exuded (I’m more into Nyro and Mitchell, these days). This doesn’t dethrone Erica Pomerance’s blessed-out one-shot You Used to Think from its perch as the defining blast of gushing ‘60s femme-folk, but it doesn’t miss by much. The bonus cuts on the CD reissue are quite welcome and show Perhacs to be a smart, versatile artist that deserved so much more than to be queened as a cult figure. I want to hear the new stuff.

WEDNESDAY 1/7- I haven’t always loved The Pogues. I remember mildly digging the Poguetry in Motion EP when I bought it back in the late ‘80s but I stupidly traded it in for I think a Phantom Tollbooth record (that I don’t even own anymore). My other run-ins with the group never really resonated with me until about five years ago. I picked up the above album used for very cheap, thinking what the hell, here’s another one for the stacks. And I’m glad I did. While I am partially of Irish descent, I’m not at all weepy over it, so ancestral nostalgia has nothing to do with my change of heart. I just seem to have grown into its charms. Where they once seemed old hat and overly theatrical, they now seem (on this record anyway) shrewd and well constructed conceptually. And pretty. And theatrical in the best way possible. Elvis Costello’s production might be a tad middle-of-the-road for my tastes, but he does nothing to sabotage the proceedings, so maybe I should just be quiet. This band’s music has been the soundtrack to so many loutish drunken nights from aging malcontents obsessing over their place in the world and the genetic stamp of their being that the industry’s of stout and whiskey should pay them a large stipend. There’s no doubt these cats sound best when you’re half blasted and simultaneously soaking up emotions like a sponge and secreting them like a spastic lawn sprinkler, but they can also be endearing on a sober cold-weather night alone. I feel so mature.

-

I’ve been connected with the music of Fred Firth for over half my life. He’s just a monster of the experimental guitar and his passionate openness to so many different types of music and his participation in a bunch of varied “scenes” made it almost impossible for my inquisitive young mind to not cross his path. I was tired of the little box that punk rock had become and was dipping into some of the more esoteric releases on SST records, Frith’s 2LP The Technology of Tears being one of the first. I was curious about The Residents, and he was a major presence on their Ralph records imprint, both as a guest and stand alone artist. I found his name on my copy of The Violent Femmes’ The Blind Leading the Naked. The more I dug into the records on Mark Kramer’s Shimmy Disc label, the more familiar he became. Indulging in Eno’s brilliant streak of ‘70s albums found him on Before and After Science and Music for Films. I scored a tattered copy of the first Henry Cow album because a fellow King Crimson fan recommended them, and discovered he was charter member. And impulsively buying the first Naked City record on cassette sealed the deal: his mark on my then meager record collection was secure, and this was completely due to his eager interaction with a bunch of musicians whose paths normally didn’t cross. Thing is, the guy is still going strong. Frith has always stood with Eugene Chadbourne and Henry Kaiser in a righteous triangle of avant guitarists that never lost touch with their non-experimental roots, and To Sail, To Sail has moments that recall everything from Fahey, Cooder, Kaiser, Bailey, and a whole lot of Fred Frith. His music has inviting warmth even at its most abstract moments, and the record generally heads into less definable territory as it progresses. It’s just him and a steel string acoustic, and the textures, tones and movement he can dash off is nothing short of fantastic. If you are a novice to his work, this would work as a start I think, but it’s also hard to not advise jumping in with Guitar Solos Volume One and the first Henry Cow record (both available on EMusic for the cost conscious). It’s coming up on forty years since he began examining and expanding the possibilities of stringed instruments, and after appearing on 400 plus recordings, he’s as vital as ever.

THURSDAY 1/8- Shark Quest should frankly be much better known. The reality of the band’s non-post rock eschewal of a vocalist and their often Americana-influenced direction certainly play a part in their lack of widespread rabid fandom, but they’re great enough to overcome these unfair obstacles and the fact that this has yet to happen is a sad state of affairs. Battle of the Loons is their debut and it displays a major helping of dexterous musicianship while keeping the lid on the pressure cooker of needless showiness. The examination of roots is evident without turning the proceedings into a phony knee-slap fest, with many moments actually holding more than just a whiff of the conservatory. This appeals to me very much, but the lack of a convenient handle might befuddle many. The deeply bowed tones on the opener “Blake Carrington” sound more New York than North Carolina, and the whole disc lacks any easy gestures to popularity. Two more records have been released without much change in their circumstances, and I can only hope they haven’t called it a day. It would be great to see them at this year’s Merge anniversary shindig, but without a new album to promote that’s not likely to happen. Maybe Shark Quest is destined for posthumous acclaim. If so, I’m going to lord it over all you mofos.

FRIDAY 1/9- This Bill Dixon release is my pick for the best of 2008. It’s been with me for months but I’m still a little scared of it from a writing standpoint. Last year’s resurgence in things Dixon was one of its most pleasant surprises. This record, the collab with Rob Mazurek’s Exploding Star Orchestra, and the sudden slew of older releases available for inexpensive legal download really put him on the radar screen as something other than just an intriguing figure in free jazz lore. Tons of people knew him as the man behind the legendry 1964 October Revolution in Jazz , and many heard him in tandem with Archie Shepp and as a member of Cecil Taylor’s smoking group circa Conquistador!, but his Intents and Purposes album for RCA from ’67 is still criminally out of print, and he dropped out of the pro music scene for academia in Vermont for such a long period that when he started recording again for Soul Note in the ‘80s he dented the consciousness of many avant-jazz fans but didn’t concuss enough perceptions to take his rightful place as one of the elders of free jazz. In Dixon’s case free is a descriptor in need of clarification, since he is foremost a composer, and Darfur can indeed feel at times like modern avant-classical. It can gather a sheer intensity that’s left me awestruck and unable to follow it up with anything but silence. The group is largely made up of fresh names and a few older, more established players like trombonist Steve Swell, bassoon player and Jimmy Lyons/Cecil Taylor cohort Karen Borca, and percussionist/vibe player Warren Smith. Shit-hot Braxtonian Taylor Ho Bynum is here as well, and the whole group possesses a collective musicality that results in devastating excursions into Dixon’s sound world; nary a note is tentative. I’m pleased as punch that this record exists, that the man responsible made the cover of The Wire, that divergent opinions are flying to and fro in cyberspace concerning him, and that his pendulum of fortune is finally starting to swing the other way. The next time some smarty tries to opine that jazz is dead I’m going to ask them why this disc made the hair stand up on my arms. Moribund music doesn’t do that. Intents and Purposes needs to become available (what asshole corporation owns the RCA back catalogue, anyway?), and hopefully Dixon has a follow up to this one in store. I’d like to see him pluck a few folks from this group and throw down some spirited improv. Or a solo disc. Or a duo with Cecil. Keep ‘em coming, Bill!

Bill Dixon

Bill DixonSATURDAY 1/10- Art Blakey’s impact on jazz is pretty much impossible to measure. He’s one of the absolute cornerstones of post-bop, and his groups featured so many amazing players, particularly in the second half of the ‘50s, that listing them is rather daunting. So I’ll just mention the names on this one. Wayne Shorter on tenor, Freddie Hubbard (RIP) on trumpet, Cutis Fuller on trombone (if the name doesn’t ring a bell, he slays on Coltrane’s Blue Train), Blue Note mainstay Cedar Walton on keys, and Blakey regular Jymie Merrit on bass. Any version of The Jazz Messengers that I’ve heard is loaded with infectious and adept rhythmic passages, but I’ve yet to cross the path of one that slides into overzealousness. I’ve thus far stuck to the more established classics, not dipping into the later releases that spanned into the ‘80s, so I can’t really venture a complete synopsis of his talents. One thing that I’ve noticed about the more canonical records is how generous Blakey was with his younger band members. Everyone has ample opportunity to shine as a soloist and to display their songbook. Two tracks are courtesy of Walton (“Mosaic” and “The Promised Land”), and we get one a piece from Shorter and Fuller (“Ping Pong” and “Arabia”, respectively). That leaves one standard, “It’s Only a Paper Moon”. The whole record simmers with the rare intuitiveness that makes the best post-bop more than just a study in chops. Blakey certainly asserts himself; the drums connect in a way that’s unique in the context of this era, but it never feels like showmanship. He’s a supreme catalyst. And everybody on this thing is catalyzed. So am I. I basically spun this one because I wanted to hear so prime Hubbard, his recent passing sticking in my mind. He delivered, but I ended up receiving a lot more for my interest. Post-bop doesn’t get much better.

And avant-garde troubadours don’t get much better than Anthony Braxton. This solo disc taped live in Germany’s Moers Festival finds him running roughshod over an alto sax with so much savvy that I’m surprised the instrument didn’t liquefy in his hands. The danger in solo improvising is running out of ideas (plus there is nobody else to provide inspiration except possibly an audience, but more about them in minute). I’ve yet to hear Braxton lose focus or intensity in the solo setting. Much like Cecil Taylor, the guy never appears to be going through the motions, and the nakedness of playing alone insures that he couldn’t even if he wanted to. The sound is at moments raw, contemplative, joyous, complex, and simple. It’s always demanding and rewarding. The crowd in attendance seemed to think so as well. They thunder out applause like a bunch of plebs pleading Pete Frampton for a fourth encore in ’78. The Germans sure know a good thing when they hear it.

SUNDAY 1/12- Mark E. Smith’s The Fall formed when I was five years old. Smith just keeps on trucking seemingly for the sheer hell of it, and the longevity has surely cost them some legendary status. If he’d quit around ’85 I feel safe in estimating that The Fall would be held in much higher esteem then they already are. I’m not accusing the populace of objectifying image and obscurity. The band has so many records out they need their own special cabinet to hold them all, and if an unschooled gal or guy gets gestured toward their stuff without specifically being guided to start early and stay late, then false impressions could easily result. Ditto to bumping into a vitriolic screed lobbed against a recent release in an internet magazine, or seeing a snapshot of his uncomely snaggle-toothed speed-damaged countenance: all of the above has likely steered more than a few folks away from the grandeur that is The Fall. Suffice to say, Pavement wouldn’t exist in anything resembling their collective reality if Smith didn’t blaze his maddeningly seductive trail. Slanted and Enchanted owes so much to their brilliance that spinning it next to the masterpiece Grotesque has no doubt dropped thousands of jaws. It did mine. Oranj is from the Beggar’s Banquet-era, which some people love and others are more blasé over. This period was my intro to the group (besides “Bingo Master’s Breakout” and a Peel Session EP), so it will always have a special place. It’s a score for ballet that’s at least somewhat concerned with William of Orange, but it doesn’t feel particularly unusual in the context of The Fall’s discography, the opener “New Big Prinz” is quite attractive, partially because Smith’s voice was so much stronger in the mix during this era, and this particular release regressed from the poppier study of the previous album The Franz Experiment (still a great album with a sweet cover of The Kink’s “Victoria”). So this is the best of both worlds in a sense. “Dog is Life/Jerusalem” starts like a sound clip from the greatest poetry reading ever held and morphs into a rather rad piece of Smith’s skewed crooning (with lyrics courtesy of William Blake), “Wrong Place, Right Time” is a righteous stomper, and the title cut is just drenched in Smith’s stammering blabbering greatness. And there’s more. If you’re a newcomer I say locate Live at the Witch Trials and get bowled the fuck over. But don’t forget about this one. It has a special appeal that hasn’t waned with time.

If you’re a Coltrane nut like I am, then you very likely already own One Down, One Up. The legit issue of this tape may not be as unexpected as the Thelonious Monk/Coltrane disc that was released the same year, having already been bootlegged, but the fact that it’s now available as an above board release adorned with outstanding Impulse! packaging is wonderful to behold. My top two live recordings from Coltrane are the scalding two discs of Live in Seattle and the behemoth monster four disc explosion of Live in Japan, and due to the circumstances surrounding this release it won’t topple either of those from their elevated status. Live at the Half Note is radio broadcast recordings that are indispensable and often incendiary in nature but suffer from attributes which diminish the whole without detracting from the overall worth of the release. The title cut, which many will know from the brilliant New Thing at Newport, is only partially recorded, picking up in Garrison’s solo, and this can’t help but lessen the impact, a bit like re-watching Two Lane Blacktop or rereading The Dharma Bums from the middle. Naturally not as good as the whole picture, but this isn’t really a fault, for what’s gained is an extended opportunity to catch a captured glimpse of Coltrane’s group in full blossom. Captured is an important descriptor, since this again was a radio broadcast, not a professionally recorded live record. I don’t think anybody involved with the music documented on this night thought for a second that forty odd years later it would be a prestige release from one of the greatest groups of all time. It’s safe to assume that this was just another night for these guys, another radio air check to be absorbed by the live audience and those with ears attuned to radio speakers, to be enjoyed or rejected or puzzled over and possibly discussed but filed away in memory banks shortly thereafter. Maybe a few dozen trips to the record store would result. Maybe some moldy fig would call up the station and complain. Perhaps two people would make love or a person sitting alone in darkness would be brought to tears. This is what makes One Down, One Up so valuable: the audio-paparazzi factor, where these four giants were working through the sound that gave them their stature in a manner simultaneously everyday and euphorically transcendent. It’s recordings like this that really separate this band from so many other estimable combos. The contents herein were just natural stuff to them, like breathing: listen and hear one of the high-water marks for humankind.

Coltrane plays on Taylor’s Stereo Drive, a weird, neglected and often maligned record. It’s well established that the young Taylor, while not then the blistering keyboard genius that flowered in the ‘60s to be perpetually in bloom ever since, was a bit above the comprehension of producers and studio execs of the era. Profit motive is the obvious factor in teaming up Taylor and ‘Trane, but it still made sense artistically. The big problem with this recording relates to trumpet player Kenny Dorham. It quickly becomes clear that he and Taylor weren’t really on the same page. All the momentum that builds up through the connection between Coltrane’s opening sax salvo and Taylor’s knotty phrasing is considerably flattened when Dorham appears and improvises like he’s at another session. Maybe he thought he was. It’s not horrible sounding, but is a bit depressing, with the occasional twitch of fascination about it. Taylor’s playing shifts considerably at these moments, leveling out because he lacks a partner to work with/against: instead he’s sharing studio space with a guy blowing straight-ahead like the Blue Note regular he was. No slight to Dorham (who I love in many other contexts) but this is just an undisputed mismatch. To see just how contained Taylor is here one need only listen to Jazz Advance, recorded two years earlier with sympathetic peers Steve Lacy, Dennis Charles and Buell Neidlinger. This was the start of it all for Taylor, and the recording still holds an electric feel that gives truth to its title. It’s interesting that Lacy and Neidlinger jumped straight into the avant-garde from trad-jazz, sounding inspired and comfortable in the idiosyncratic atmosphere of Cecil’s keyboard construction. Many groundbreaking recordings eventually lose their front-line qualities as time passes to either sound classic or quaint. Jazz Advance still holds considerable edginess, largely because Taylor’s piano is so singular, with the added fact that his cohorts on this session were truly involved in making it something timeless.

No comments:

Post a Comment