In the early 70s, Richard Meltzer began his slow journey away from rock criticism by submitting reviews that only dealt with the record's packaging, filling column space not with the dreary prose that his editors had come to expect and actually demand, but instead fixating in his canny and dyspeptic way on the minutiae of what had become almost integral in the atmosphere of the "business" of rock music, i.e. something that's unquestionably important yet almost never gets talked about. Because if "it" wasn't important, the "it" being the album cover, than they'd certainly all look the same. Important to whom, you might be asking? That's a big question, but for the purposes of this argument, the ogre of "financial interests", most definitely. Now, it's easily evidenced that album covers don't look the same. But "feel" the same? Oh yeah, at least a significant portion, and I'm not talking about the sensation of holding them in your hands, natch. When album covers begin to feel the same, what's that say about the music inside? Now, the roomy tract you're currently reading isn't going to follow Meltzer's paradigm very closely, but I wanted to mention him now because we'll return to him later. For the time being though, let's talk about Raymond Pettibon, the artist responsible for the cover of MY WAR.

Raymond Pettibon

In my eyes, one of the most interesting angles in the whole underground music milieu is the Who, What, and Why of the scene participant's various non-musical interests. Pettibon’s contribution is frankly one of the most appropriate alliances (in terms of style and subject matter) between music and visual art formed in the "punk" movement, yet this connection can prove rather elusive to easy synopsis. He is essentially an artist of discomfort, and his art is suffused with negativity and a profound preoccupation with bleakness and despair that made its adoption by the counterculture of the Reagan-era almost inevitable (and it surely helped that Pettibon was Black Flag guitarist and SST owner Greg Ginn's brother). However, the large bulk of his art from this period features so much depth and bitter intelligence that I can't help but think it was lost on the majority of those who felt it was "theirs". Or to put it another way, I can't shake the suspicion that so many were stoked over the shock value while sidestepping the critique that often concerned their contemporaneous social environs. But maybe I'm judging to harshly. One of the unique aspects of the punk/indie scene's extra-musical influences is how diverse they were. This fact often takes people with even a fair knowledge of this era's music by surprise. The lack of overt documentation on the specifics of what was happening in film, writing, and visual art within this subculture can lead some individuals to conclude that John Hughes films and Bret Easton Ellis novels were primary exponents of the period's underground rumblings.

To be blunt: Au contraire. Legitimate non musical contemporaries were definitely making contributions to the cultural landscape. The written word was represented by such disparate entities as Kathy Acker, the cyberpunk sci-fi of William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, and Lewis Shriner, the late works of William S. Burroughs, musician littérateurs like Nick Cave, Lydia Lunch, Billy Childish, Chris D. and an inked-up baldy whose birth name was Henry Garfield; film was infested by Cinema of Transgression figures like Nick Zedd, Beth B. and Richard Kern, along with other names like Dave Markey and John Moritsugu; and visual art saw the paintings (and performance works) of Joe Coleman, the woodcuts of Billy Childish, the scrawl of Savage Pencil, the cross-media gestalt of Gary Panter, and of course a venerable gaggle of commix artists venting spleen and acting snide or aloof, probably the most successful example being a guy you may have heard of named Matt Groening. Raymond Pettibon falls into this sticky constellation, his personal aesthetic radiating like hijacked James Thurber one panels that have all the humor sucked out of them only to be injected with trepidation, existential dread and flashes of misery. Of course, punks and other non-conformists of this era (read: bohemians) also grabbed from history, and it's rather startling just how intense this plundering was. Contrast this to the hippies, where the distrust of older generations meant that only very specific artifacts were allowed entry into their playground (some Beats, some Huxley, and some Hesse, for example) and you can see just how non-rigid the '80s subculture really was. Lit kicks were satiated from sources as various as those Beats, hardboiled detective fiction, pulp sci-fi like Phil K. Dick and Samuel R. Delaney, post-mod word-fuckers like Pynchon, weird smut like Pauline Reage and De Sade in appropriately tough translation, pimp pulp from Iceberg Slim, Hubert Selby's sustained scream from the New York streets, Bukowski's fly in the ointment aesthetic, French absinthe poets and their sexually transgressing country folk like Jean Genet and certainly Georges Bataille. The pilfering of visual art was just as widespread: Dada and Surrealism, the less celebrated works of Warhol and his Pop-Art brethren, Chris Burden's bonkers performance pieces (amongst other things, he was shot in the arm from five feet away and nailed to the back of a Volkswagen; now THAT'S an example of the utilization of shock value that I fully endorse), and the equally berserk activities of the Vienna Actionists. But looking at film provides the most enlightenment into '80s bohemia's rabid selection. The explosion of home video viewing and the proliferation of midnight movie showings really boosted the situation. A hypothetic book on the subject could be broken down into the following chapters and would in no way be exhaustive: the blunt strangeness of Tod Browning's FREAKS, the early surrealist revolts of Luis Bunuel, Nick Ray's REBEL WITHOUT A CAUSE, oddball Hollywood and independent sleepers like Samuel Fuller's THE NAKED KISS and Leonard Kastle's THE HONEYMOON KILLERS, the films of Jean-Luc Godard (particularly the more difficult work like WEEKEND and SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL) and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, the Psychotronic phenomenon from Ed Wood to H. G. Lewis to Andy Milligan, the gut-punch horror films of George Romero, Tobe Hooper and Wes Craven, idiosyncratic midnight movies like Lynch's ERASERHEAD and Jodorowsky's EL TOPO, controversial works by established commercial directors such as Kubrick's A CLOCKWORK ORANGE and Scorsese's TAXI DRIVER, the films of John Waters and Russ Meyer, early Cronenberg, Andy Warhol's directorial efforts and those he produced with Paul Morrissey, and the avant-garde work of Warhol's contemporaries, particularly Jack Smith’s FLAMING CREATURES and Stan Brakhage's sublime autopsy film THE ACT OF SEEING WITH ONE'S OWN EYES. In addition to the simple availability of all this stuff were the long gaps in the emergence of contemporary work that could speak to this alienated and self-marginalizing audience. Sure, in addition to those mentioned a bit earlier there was Derek Jarman and ROCK AND ROLL HIGH SCHOOL. Yes, there was a spate of non-fiction films that documented the scene. Alex Cox’s REPO MAN obviously deserves mention along with other unusual “Hollywood” films like Dennis Hopper's loopy OUT OF THE BLUE and Tim Hunter's THE RIVER'S EDGE. We can throw in “message-porn” like CAFÉ FLESH and the druggy/arty sci-fi of LIQUID SKY. But before long it starts to be slim pickings, in part because the distribution networks were more grassroots in this era. What's this have to do with Ray Pettibon and his cover for "My War"? Well, nothing. And yet everything. NOTHING because the last three paragraphs were essentially just a riff (I love jazz), an indulgence (so does Pettibon), a way of fleshing out some of the cultural terrain of a period where everything wasn't available at the click of a mouse, and people were forced to bring dimension to their way of life through constant digging and the passing around of artifacts while the culture at large looked in the other direction. It was so much more than mail ordering records. And EVERYTHING because context is essential; Did you know Pettibon also made films?

VHS cover to Pettibon's CITIZEN TANIA

He's been in bands, too (he's in one now, in fact). And his art for many years was collected into little low-budget pamphlets that could be ordered direct from SST. These small books could be used in a variety of ways; carried in backpacks and stared at in cars while waiting for something (nothing) to happen or strategically placed in the living space to ultimately trigger a reaction. Upscale trendies aren't the only people with coffee tables, you know. If there is a certainty in this universe, it is that PUNKS LOVE COFFEE, and I'm just as positive that one of Pettibon's chapbooks would look flat-out amazing next to a piping mug of shitty instant brew. But really, my digressions do at least provide emphasis that this specific movement generally disdained art that had any real relationship to fine-art aesthetics or any high (or middle) brow acceptability. Take photography for example: The main thrust of it within this scene was divided between stern documentation (Glen E. Freidman, SST's Naomi Pedersen, Jenny Lens, Cynthia Connelly, and later shutterbugs like Michael Levine and Charles Peterson for example) and the eventually stultifying application of collage art (more Dada influence) as statement (we could maybe call this the Maximum Rock 'N' Roll aesthetic). Art photography seems rare in the annals of the era, the only names really springing to mind being Robert Mapplethorpe, Joel-Peter Witkin, maybe Larry Clark (later of KIDS directorial fame) and possibly Robert Frank if we're being extremely inclusive. This isn't to infer that documentary photography lacked an artistic dimension (no way) or that the occasional collage didn't achieve its effect. I'm just trying to ram home the point of just how anti-establishment this movement was (and still kinda is, because I tend to look at the period between the counterculture's re-ignition around 1977 and the present day as one long and warped continuum) in relation to its defining principles. If the public at large is generally thinking glamour shot sheen or Ansel Adams (glamour shot mountains) in relation to photography, then it's no surprise that the post-'77 scene so thoroughly embraced a basically vérité approach. To extend this idea: When an ink on paper piece by Pettibon commands $66,000 at auction, it's impossible to think this won't somehow change how his art is perceived. In this case, his work had certainly developed but suffered no commoditization (i.e. sell out); it is simply the case that museum culture reigned him in as one of their numerous outsiders. But dig what happens when this occurs: the joy that's inspired by the strange reactions and dismissive tut-tuting over a freaky album cover is replaced with the feeling that smartly dressed people with too much fucking money have co-opted another goddamned thing.

Sour grapes over losing exclusive bragging rights to the fandom of some record/film/book/etc is generally not very attractive, and I tend to take a more pragmatic approach and cheer when some little niche artist/writer/band that I love finds a wider audience. But sometimes it's hard to not feel the sting. Like when an old SST mail order catalog falls out from an LP sleeve onto the carpet, for instance. I pick it up to ogle the listing for once affordable Pettibon chapbooks, and that leads me to look across the room at the thick and glossy paperback of his awe-inspiring later work that set me back $80. Damn right I feel the sting. But that's okay, because when that baby sits on my coffee table it looks just beautiful.

One of the positive things that Pettibon's integration into the art-world has inspired is a more accurate view into what it is exactly that he does. If I had a buck for every time I clarified to someone between 1988 and 1995 (an arbitrary cut off point, sure) that Pettibon wasn't a cartoonist or comic (or commix) artist, I'd buy you lunch. No, not you, YOU. It'd be cheap eats, but still. Pettibon was sometimes mistakenly lumped in with such u-ground comic scribes as Charles Burns, Dan Clowes, Wayno, Kaz, Los Bros Hernandez, and Peter Bagge, but what this wild-assed group did was basically adapt their working methods into a piece that could help an album sleeve or CD cover stand out from the majority while basking in the good vibes (and personal checks from record labels) that mutual appreciation inspires. The use of Pettibon's work is essentially different. The impression is that he worked on his own and his pieces were later adapted (and rather notoriously debased with scissors) to gig flyers and album covers. On one hand he's identifiable as an artist in isolation, yet he designed the Black Flag bars, which lends him the aura of collaboration. The work of the comic artists always felt more capitalistic than that: Clowes was quite blasé about it in interviews and Burns and Bagge submitted work for some really rotten mainstream albums. In the '90s there was an explosion of artist collaborators like Frank Kozik and Coop who seem more in league with Pettibon, but here the difference is less one of function and more one of effect. Both Kozik and Coop were all about the reinterpretation and subversion of iconography, the former turning established and seemingly benign images like cartoon characters into drugged out sex kittens or creepy street urchins, and the later ramping-up old standbys like salivating sex-crazed wolves, making the object of their lust-drenched blood-shot eyes the buxom and scantily clad women descended from hot rod culture that radiated like a twisted manifestation of R. Crumb's gargantuan libido.

A nutshell example of Coop's style

This duo was one of the prime examples of the ‘90s’ sub-cultural fascination with being politically incorrect, or more accurately they filled a need by some to adopt a deliberate stance that prized a type of apolitical hedonism. In addition, Kozik and Coop were essentially about surfaces and are basically formalist. They both actually sort of defy the punk ethos that anybody can play. One look at their work shows that a high level of discipline and trad-art skill was employed, even when the deluge of silk-screened show posters, magazine covers and limited edition record sleeves began to take on an almost Warhol-like assembly line feel. There was actually a bit of grumbling about Pettibon during this era, even from Kozik himself, the main thrust being that his stark, often minimalist work possessed a lazy, sloppy aura that a more precision-tuned artist like Kozik found unappealing. I took this in stride then and now, but still feel that it's similar to the attitude that The Ramones weren't any good due to their music's lack of solos. But the ultimate proof in the pudding regarding the difference between Pettibon and Kozik/Coop/etc is one of impact. Again, the more formalist approach of the later group never really gets beyond the level of eye candy, which is cool enough, but there was just so much of it on CDs and posters and the covers/pages of YOUR FLESH that it seemed the scene eventually OD-ed on the stuff.

It was everywhere for a while, then it suddenly wasn't. In contrast, Pettibon was never really that prolific, and an even better point would be that his work is so wrapped up in his personality and ideology that he never had a single imitator. And Pettibon's art has a depth that really lingers. The effect of a piece viewed once can last years, and other examples can put a damper on my day (in the best way possible) even if they are already quite familiar. Pettibon may not be the cause célèbre he once was, and his audience may now include wealthy art investors who don't give two squirts about the aesthetic worth of the So Cal punk rock scene that helped thrust him into prominence, but his presence is certainly still vital.

So there we have it. And in an attempt to not sound like a panting sycophant, I'll refrain from giving too much credit to the SST crew for their adoption of Pettibon's work as a visual signifier. The blood relationship between Pettibon (pseudonym from the French, petit bon, and meaning "good little one": thanks Wikipedia) and Ginn makes downplaying rather easy, plus the rather offhand way that some of the SST crew approached Pettibon's art doesn't smack of a reverential mindset to the man's stuff. I'll stop short of describing the appropriation as trying to just shock and instead opine into what I think was really being attempted: the desire to stand out in a field that was beginning to look and feel the same. You can apply this idea to the band's hairstyles and clothing choices as well. Countercultural conformity was starting to run rampant, and Black Flag really defined themselves as not belonging to any camp, and if there is any artwork from that era that promulgates alienation and the ideals of being a loner, it's Pettibon's. But in contrast to how the Minutemen used his work, Black Flag's collaboration, while certainly subversive, still seems significantly less profound. To relate this back to Meltzer, the whole punk rock impulse, and the west coast division of it in particular, actually got him inspired again by the potential of basic, dirty rock 'n' roll as a vessel of defiance and distorted beauty.

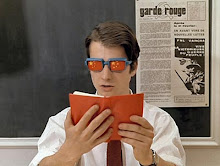

Meltzer reading publicly a few months back via Kevin Sampsell's blog

The contrarian streak never left him, but he hosted a radio show for a while ("Hepcats from Hell"), penned a whole bunch of rock related junk for small press publications throughout the '80s, talked some sweetly foul mouthed shit about Bill Graham's Mom on stage as the emcee for the Sex Pistols' final gig at San Francisco's Winterland Ballroom, fronted the blink-and-you-missed-it punk band Vom with the future Angry Samoans, and inspired D. Boon to proclaim from the stage: "This song goes out to Richard Meltzer, he was our hero!". Righteous and individualist tactics like submitting cover art-centric record reviews to publications whose modus operandi was nothing more than insuring their print pages secured record company advertising was just one thing that made him so heroic. And that heroism manifested itself in the way SST operated (at least early on), which in turn impacted my teenaged consciousness as I ominously eyeballed the covers of MY WAR, SLIP IT IN and LOOSE NUT in a sterile mall record store, where they frankly stood out like radioactive artifacts in an ocean of insubstantiality. I can only hope that some impressionable upstart might stumble upon this modest bout of theorizing and get gobsmacked by the mighty inksmanship of Raymond Pettibon, and in turn elect to spend his life asking questions instead of dully and dutifully accepting the answers. We can only pass the torch one person at a time, right?