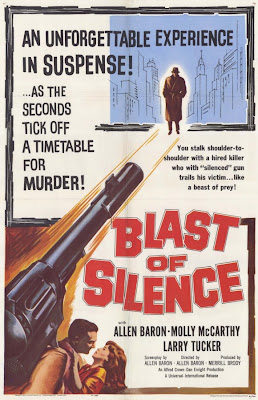

BLAST OF SILENCE (1961, Allen Baron) - The Criterion Collection continues to be a fantastic resource for things cinematic, particularly little orphan films like this one, a cult item from the tail-end of the original noir cycle that’s been talked about so highly and for so long it frankly had a large reputation to uphold, due mostly to my naturally raised expectations (a fate very similar in my personal trail of film discovery to Leonard Kastle’s classic one-shot THE HONEYMOON KILLERS). BLAST OF SILENCE is certainly a quirky film, featuring an interior narration that serves to amplify the solitude and disgust of the main character, a contract killer (played by the director) who goes coldly and deliberately about his business until the hands of noir fate start to gum up the works. But the unusual narration is hardly the only element of the film that stands out; the period flavor of New York City and certain landmarks (Harlem and the Apollo Theatre, the Village Gate nightclub, etc) is so thick that it virtually becomes another character, and the visuals lack the polish of even most B-grade Hollywood noir yet are smartly filmed and edited. Yes Martha, this is surely low budget stuff, and the acting often lacks the professionalism that helps to ground even modest studio filmmaking with a degree of perceived ‘normalcy’. That’s not to say the acting is ‘bad’. Most of the players had obviously acted before, and they are believable in their roles; it seems more likely that the non-polish on display had more to do with tight shooting and lack of retakes. One actor does stand out, though. Larry Tucker plays an obese, bearded hoodlum and achieves a formidable level of weirdness. The movie is worth watching for his performance alone, but it’s even better that Baron was able to integrate the actor’s energy into his mise en scene with such success. There is definitely some impressive raw inventiveness going on in BLAST OF SILENCE, particularly the nastiness of the violence, the anti-social nature of the hit man (and how his one attempt to reestablish contact with someone from his past throws his whole world out of balance), and an ending that uses its blunt inevitability as strength - i.e., you can see it coming a mile a way, but this knowingness of what’s going to happen adds a fine sum to the film’s total equation. Yeah, by the end, I was hooked. This is as fine a piece of left-field, no-sheen filmmaking as I’ve seen in quite a while. Now that I have actually watched it I guess Irving Lerner’s MURDER BY CONTRACT moves to the top of my most salivated over rare films noir list. And that one’s currently available. What an unlikely twist of good fortune.

THEY LIVE (1988, John Carpenter) - This one has grown into a solid ‘cult’ item, and deservedly so. It’s hard to think of a better example of a smart movie (in both content and form) lurking in the folds of what so many perceived as just another silly action flick. Carpenter’s work is probably never going to be championed by high-brows (at least not in this country), but that’s their (our) loss. Of course, the director deliberately muddies the waters by working at extremes. On one hand, his ideas about consumerism and societal conditioning are blaringly clear, yet they are delivered through a genre piece that’s usually reserved for popcorn-movie escapism. He rather subversively casts pro-wrestler Roddy Piper as his lead actor, for crying out loud. What’s lastingly great about this movie is how the direction never sells the content short. On the contrary, by using the story device of the truth telling sunglasses, Carpenter is able to utilize formal elements to really push his themes to strong levels without weakening the story’s tight construction. So, he can make a BIG point without the viewer feeling like s/he’s been clubbed over the head. The sharp contrast between the rather conventional progression (in the Hawksian sense) of the film up to the moment where Piper puts on the sunglasses and how the narrative momentum is momentarily derailed while our protagonist gets smacked with the blunt black and white reality of subliminal mind control just screams to be experienced in a darkened movie theatre. From the point of this all important discovery the movie delves into some darkly comic playing around with genre tropes (particularly a fight scene that expertly flirts with parody and one of the hammiest lines of dialogue ever delivered) before boiling down to a fine riff/update on 50s-style sci-fi belief stretching and concluding in a rather abrupt, oddball ending. Yeah, it’s a humdinger. But again, the real strength in Carpenter’s work lies in its economical, concise construction: the image of a piece of cash currency holding the words ‘THIS IS YOUR GOD’ is just a visual grand-slam, for it says in a few seconds what Oliver Stone’s ‘Wall Street’ spent over two hours agonizing over (and paradoxically unwittingly glamorizing). Within Carpenter’s razor sharp oeuvre (up to around the end of the ‘80s, anyway), this is top four, easily.

NASHVILLE (1975, Robert Altman) - I’ll cop to not having watched all of this film until something like my fifth attempt, even though I really like many of Altman’s films quite a bit. This is over two and one half hours set in the city of the movie’s title that concerns characters that have some sort of relationship (either entrenched or peripheral) to the city’s country music scene. There is also a ‘third-party’ political campaign that features in the story, and the way this connects to the city’s music business and the characters that populate and surround it is a basic canvas that ends up growing into a wall sized mural by the film’s end. Altman can be smug and condescending at times, and the population of his ensemble cast unfortunately doesn’t hold anything resembling equal importance in the story. Unfortunately, much of the short shrift goes to women. Shelly Duvall’s character, an anorexic interloper from California, is essentially a mean-spirited joke that basically just requires her to walk around either in ‘wacky’ clothes or her underwear, and Geraldine Chaplin’s BBC reporter becomes increasingly hard on the nerves as she alternately stereotypes what she perceives as clueless simple folk and amateurishly philosophizes about what they ‘really’ signify. But the cynical 70’s Altman is never without bountiful rewards. The film doesn’t really have a plot; instead, it uses a gradual accumulation of group activity to impart essential information as to where the film is going and to explain the motivations and personalities of the characters. Along the way, actors who play the part of performers sing songs that they often wrote themselves (Karen Black’s being the most interesting/successful), and the rather strange vibe of the whole Hal Phillip Walker political campaign really settles into the general fabric of the film. How the presidential candidate is represented in the movie is a shrewd formal device. We never actually see him, but we sure as hell hear him, due to a megaphone wielding van that travels the city blaring out the man’s calm screeds of ‘populist’ dissatisfaction (that seems to obscure the ogre of grassroots fascism). Michael Murphy’s campaign manager does appear however, giving the lie to Walker’s platform, and in doing so balancing the sense of political apathy and resignation that is best represented by NASHVILLE’S gospel tinged denouement song ‘It Don’t Worry Me’. In the context of the movie, the song represents a snide commentary on the post-60s feel-good political defeatism that’s being propagated in the film by a folksy trio seemingly based (loosely) on Peter, Paul & Mary. As the true nature and motivation of Murphy’s character comes into focus, so does the thrust of Altman’s film. The idea that corruption infects everything it comes in contact with, causing either more corruption or deflated acceptance/lack of resistance is certainly representative of the 1970s mindset, both artistically and culturally. By the ending (which I won’t spoil if you haven’t seen it), Barbara Harris’ success-crazed character is on Nashville’s Parthenon steps (the concept of the city as ‘Little Athens’ is tellingly mentioned by a character) belting out the aforementioned tune, and every time she wails the song’s title what she’s really saying can be summed up as follows: “EVERYTHING (AND EVERYBODY) IS FUCKED. We might as well just sing about it (READ: sing ‘around’ it.)” Probably not the best movie to watch during an election year (particularly on those occasions where you’re faced with the lesser of something or other), it still rates as a flawed and sprawling masterpiece. Altman definitely bit off more than he could comfortably chew (at the Big Banquet of Cynicism), but I’ll take that over the work of filmmaker’s who seem reluctant to even nibble at the hors d’oeuvres table (at whatever ideological feast they find themselves attending), and in turn leave me famished for something in which to sink my teeth.

THE BAD NEWS BEARS (1976, Michael Ritchie) - So sports movies almost always suck. Bio-pics are about the only type of film that has a lower success rate in my personal estimation, and when bio-pics are done on sports figures, you can almost guarantee that the result will stink up the room (an exception would be Scorsese’s RAGING BULL, though it’s arguable if bio-pic is really the appropriate descriptor for that discomforting masterpiece). This movie isn’t a bio-pic, natch, but it does concern a little league baseball team, and it’s one of the first films that I can recall watching as a kid. I hadn’t thought much about it until recently, when I caught some of it on cable, and found myself pretty wrapped up in it, party due to sentimentality, but also because it’s sort of an aberration. The movie is not so much about sports. It’s really about the desire for winning growing into a disease, and also about the emotional and physical damage that kids and adults inflict on each other (and themselves). I found a cheap DVD of this for sale and impulsively bought it, curious as to how the whole film held up. I don’t regret spending those six bucks for a second. Now I must confess ignorance regarding the other films by this director, but reading about his 70’s work brought up a recurring theme: competition. Previous to this movie, he’d directed a duo of films with Robert Redford, one about skiing (DOWNHILL RACER) and one about presidential politics (THE CANDIDATE), then followed that up with a commercially unsuccessful feature about beauty pageants (SMILE) that has some critical admirers. I’d really like to see that one. But what does BEARS have other than nostalgia for my younger days? Quite a lot, actually: the movie is visually assured but modest, which fits the story. The outdoor scenes often have a sun drenched dustiness that’s appropriate. The vast majority of the movie takes place during the daytime and while my observation about that is rather blunt, I’ll make it anyway: Ritchie is determined to shed light on both the nature of his cast of characters and the environment they find themselves in. It makes perfect sense to place nearly all of the narrative in the sharp brightness of daylight, where the actions of the people and the harsh reality of the situation are on full display. There are also some very effective shots, successions of shots to put a fine point on it, of character’s observing, listening, and reacting to the words and actions of others. Walter Matthau’s alcoholic team manager is fascinating: in a less complex film he would be a flawed yet angelic character who takes a group of inept misfits under his wing and in the process warms the hearts of the audience while becoming a better person. Not here. Morris Buttermaker only takes the job because he’s getting paid (bottom-feeding opportunist) and proceeds to drive the hapless group of kids around while drunk, at one point passing out from sheer inebriation on the field during a practice. His dugout rants are the antithesis of feel-good audience manipulation, and again, the reaction shots of the kids are infused with a sharp passivity. They’ve heard it before, but now it’s coming from someone who’s supposed to be on their side. Due to the inclusion of two talented players, the Bears slowly improve and improbably but inevitably end up in the championship game, where Ritchie gets the opportunity to integrate his thematic and visual ideas with real success. The game unwinds slowly, giving the illusion of real time. This helps adequately situate the actions of the characters, particularly the two adults, Buttermaker and the opposing manager played by Vic Morrow. Morrow is surely the ‘bad guy’ in the film, but his success at winning is the only thing that really allows him to play that role effectively. Buttermaker is a loser, but he’s also a lout, and at one point he angrily showers the Bears’ female pitcher (played by Tatum O’Neal) with beer when she won’t stop trying to orchestrate some off-season activities between her and him and her mom (who happens to be Buttermaker’s ex-girlfriend). All she wants is some adult stability (some normalcy) in her life, and for her troubles she ends up with a noggin soaked with suds. Ritchie’s world isn’t one of heroes and villains. Instead, it’s loaded with winners and losers. Often they do the same things, but the blatant objectification of success (and how that bleeds over into how people treat others) gives the actions of the winners a distasteful effectiveness. His losers aren’t noble as much as they are lucky. They get the opportunity to learn some important things before the druggy rush of success somehow finds them and dulls the chance that they will navigate the progression to adulthood with some semblance of human decency intact. In THE BAD NEWS BEARS, the grown-ups are pretty much a lost cause. The hope for the future lies with the kids.

MY BLUEBERRY NIGHTS (2007, Wong Kar Wai) - critical reaction to this one was generally not good. Wong Kar Wai is a Chinese director based out of Hong Kong who had a boost of notoriety a few years back due to the fandom/advocacy of Tarantino, who released Wong’s CHUNGKING EXPRESS under his ‘QT Presents’ series. This is Wong’s first film based in the US, and it seems that most of the movie’s detractors have a problem with the application of the director’s slow, lush style to the American setting. For me however, this reality is what makes the film so interesting. The story: A woman (Norah Jones) has been dumped by her boyfriend. She meets a café owner in New York (Jude Law) and drowns her sorrows in his menu. Then she lights out for the road, ending up in Memphis where she works two jobs, diner work and bartending, in an attempt to save money. She meets an alcoholic cop and his estranged wife and is witness to their problems. She writes postcards to the café owner back in New York. Then she ends up out west, working in a casino, where she meets a callous gambling woman (Natalie Portman) who asks her for money. They end up traveling together for a while before parting, and the story concludes back at the café in New York. Wong tackles the American road movie genre without sacrificing what makes his films intrinsically his. He never ratchets up the momentum, elects to avoid the detailing of traveling to instead spend more time focusing on the atmosphere of her destinations, and gives meaning to objects (keys, food, plastic chips) that flies in the face of the more conventional ‘road movie’ signifiers (cars, pavement, radio). Most people seem to view the disjointed nature of the movie as a failure, probably due to the lack of any great insights on Wong’s part. Yes, he plays around with road movie tropes, but ultimately this is a love story. Love stories in the movies were old hat before talking films were perfected. But again, Wong screws around with the convention of the love story. For Jones’ character to actually, legitimately fall in love with Law’s character, she has to end up on the other side of the goddamned country. When they first meet, she’s hurt and preoccupied with the guy who’s just told her to get lost, and instead of filming a story about two nice people who eventually fall in love due to their proximity to each other (with misunderstandings, emotional pyrotechnics, and other hijinks in evidence), Wong instead wisely separates the two. Law’s character stays stationary in his café, which is just how it should be. He knows what he wants, but was smart enough to know better than to pursue any sort of deeper emotional interaction with her at the beginning of the film. She’s deep in the messiness of ‘On The Rebound’, and she quickly spirals out of New York and under the pretext of ‘working excessively to avoid thinking about her situation’ (which happens to be the exact opposite of ‘checking in to see what condition your condition is in’, har-dee-har-har), she actually absorbs clarity and emotional stability from the difficulties of others. All of this is filmed with a non-judgmental distance that I find refreshing. That might be the final blow that has heaped this film with such disfavor. One thing American movies do far to fucking much is present situations where the audience is intended to root for certain characters and disdain others, and in the process judging the former as worthy of admiration and praise and the later as deserving disdain or opprobrium (Where does Wong get off coming to this country and making some weird riff on road movies that instead reveals itself to be actually a love story but we actually don’t know that until the end and where’s the fun in that, especially when he doesn’t even have any bad guys?). This is not to say that his characters don’t change. Wong expertly shifts sympathy on the Memphis couple without ever sacrificing the film’s tone. And the gradual layering of Portman’s character is also well done. In conclusion, many have said that with this picture Wong had ‘lost it’, but I just can’t agree. What he did by making a movie in the USA wasn’t doling out more of the same. This film is unique in Wong’s oeuvre, and it’s also unique in the landscape of recent English language film. It’s not as great as Wong in full Asian mode, but I don’t think it’s intended to be. In its low-key aspiration, I think it succeeds mightily.

No comments:

Post a Comment