By the time I’d found out about her, Poly Styrene was already long established as one of the all time great punks. As a member of X-Ray Spex, she was an integral part of barrier breakdowns concerning music and gender, and the quality of her efforts spanned far beyond the realm of the early punk scene to inspire legions of rock women. I’ll never forget the first time I heard Bikini Kill’s early self-released cassette; the emphatic jolt I received, particularly from “This Is Not a Test” and “Double Dare Ya”, was immediately recognizable as the same rush of adrenalin I experienced when discovering “Oh Bondage! Up Yours!”, and the overt influence was instantly apparent. It was one of the numerous cheap-o punk compilations that littered the racks back in the late ‘80s that provided me with my inaugural taste of X-Ray Spex’s raging debut, and what is still clear as crystal in my memory is how that track stood out amongst the other high quality contributions to communicate a direct, righteous vision. They instantaneously shot to the top of my personal Brit-punk class, joining such names as The Damned, Buzzcocks, Alternative TV and Wire. What’s historically significant is that within the solid base of personalities that contributed to “Bondage”’s success, the liberating wail of Poly and the harried reed honking of Lora Logic’s saxophone led the way. Upon Logic’s early departure to form the amazing post-punk cornerstone Essential Logic, the focus of X-Ray Spex’s delivery changed somewhat, shifting from the liberating explosiveness of that introductory blast to present a mixture of alienation and fascination with rampant consumerism that still sounded defiantly punk (and this atmosphere of self-criticism of life in the marketplace is a big part of what differentiated Styrene’s artistic personality from Kathleen Hanna, Tobi Vail and Co's tumultuous and very necessary feminist anger). The group’s debut LP, 1978’s “Germ Free Adolescents”, is mostly culled from numerous singles, but it coheres into a powerful musical statement, expressing an advanced, throttling sensibility that included knowledgeable detours into prickly, near poppish territory. I bought a used copy of the record in the ‘early ‘90s and for roughly a decade it was a frequent visitor to my turntable. Lacking Logic’s contribution to the debut 7”, it was rapidly obvious that Poly was now the dominant creative force in the band; while the rhythm section of Paul Dean (bass) and BP Hurding (drums) are spot on in terms of inspired simplicity and Jak Airport’s stellar guitar is as solid and yet fleet as a duckpin bowling ball, the motivating creativity of the unit clearly belongs to Sytrene. Logic’s replacement on sax Rudi Thomson really assisted the band in standing out in a sea of three chord wonders, but once the strength of his instrument’s unique properties became familiar it shifted from its early leadership role.

The show unmistakably belonged to Poly, and if that sounds out of touch with the tenets of punk, I’ll add that the truly exceptional examples of the style rarely followed the form’s perceived rules. And if Poly Styrene had self-contained her abilities into agreement with some illegitimate concept of band equality, she wouldn’t be the icon she is today. And the magnificence of that status was terrifically broad. She was one of the most triumphantly galvanizing examples of the punk vocalist as vessel of forward momentum, and yet her understanding of pop dynamics heralded her as a real breath of fresh air, at times almost like Debbie Harry’s smarter, snottier, more original younger sister. This fact helped distinguish her iconic status; she was human and approachable as one of us, not a person whose persona promoted admiration from a distance. A couple years into the new millennium I augmented my by then well loved copy of “Germ Free” with Sanctuary Records’ expanded 2CD set “The Anthology”, desiring to hear its addition of stray singles tracks and demo material, and it was a wise acquisition. The package did radiate that mixture of exhaustive documentation and chilly consumer desires that cloaked legions of historical releases from the CD era, but in this case the mercantile aura actually felt somewhat in keeping with the conceptual strategy of the band. Yes, the three additional single sides are a pip to hear (particularly “I Am a Cliché”, “Bondage”’s flip side), though I would’ve sequenced the first disc differently, opening with the debut 45 and then presenting the album, leaving its original integrity intact, and from there sticking the three other previously released cuts before the demo material. The disc’s roughly chronological strictness is legitimate, but it’s frankly not how most listeners absorbed the group, and it completely ignores the fact that X-Ray Spex were one of the few punk bands in the original wave that had enough high quality material to manage an album, much less a classic one. Since copyright is a weird and confounding beast, there is the possibility that while the label owned the right to release the music it was legally unable to place the tracks in the order of “Germ Free” or even reference that album, so I shan’t protest too loudly. Fuck it, I won’t protest at all. How unpunk of me. The unreleased demo stuff is worth the effort, mostly for the rough mixes with vocals, if ultimately non-earth shattering; here’s a case where the demos really feel that way, particularly the instrumental tracks, which prove just how vital Styrene was to the band’s success. The non-vocal take of “I Can’t Do Anything” could certainly inspire the belting out of some truly bonkers karaoke replete with Poly’s deliciously oddball lyrics (“but I hit him back, with myyyy pet rrrrat”) and a frothy sea of the rolling letter r. The real treat however comes on disc two in the form of the blistering aural residue from their second ever live gig, eight tracks (technically seven, “Bondage” is reprised) that include a false start, a peculiar mix (bass at times way out front), and a sloppiness distinct from the loose yet always on the money quality of the studio work.

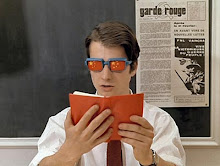

X-Ray Spex in the Lora Logic-era

But it stands as a riveting and exceedingly rare example of what a (highly idiosyncratic) punk band sounded like in live performance in ’77. Styrene had yet to fully flower, but she was in no way tentative, and if Logic at this point was the band’s most developed musical property, well that was only temporary. The package culminates with three tracks from a reunion release, 1995’s CONSCIOUS CONSUMER, and the difference is striking. If in ’77 and ‘8 X-Ray Spex were a beacon of elevated competence, nearly two decades later they were quite pro in execution. This is to be expected. As people play they get more adept, and that Poly and Co weren’t trying to approximate their early sound was admirable. There was a lyrical adjustment as well. One of the largest themes of the early lyrics was what we buy and how it shapes our attitudes, and it was mostly a critique of an outside, often public thing (to me, it seemed an ongoing debate over the idea of individualism as something that could actually be tangible, visible). By ’95 her thoughts on the effects of consumer practice had developed into what we put inside our bodies: “Cigarettes”, “Junk Food Junkie”, “Peace Meal”. And with this came a shift in the lyrics to the more tried-and-true mode of punk rock belief sharing. I can’t deny that on one hand I find this ideological solidification less appealing than the ragged searching and questioning of the early stuff, but again it’s better to see change in action than simple carbon copying. If those three songs didn’t add up to a sum that inspired me to purchase the entire album, that’s ultimately no big deal, and it’s certainly less of an issue than the band faking it/going through the motions, which would’ve been a betrayal of their early work. But it shouldn’t have been a surprise that Styrene would favor growth over stale simulation. For back in 1980, after her dropout from and the breakup of X-Ray Spex, she released her first solo LP TRANSLUCENCE, a document that shed all surface evidence of her still smoldering punk past.

I first heard this record courtesy of an older fellow record hound shortly after buying “Germ Free Adolescents”, and the difference was bewildering. How could this punk paradigm have switched so quickly to relaxed, at times borderline mellow, exotic pop? I thanked my pal for the listen (she played it for me twice), but I’ll confess to not searching for my own copy. It was quite a few miles away from where my musical sweet-spot was located at the time, frankly. And I’ll add that I never once saw the thing in used bins. This might be due to its release on United Artists, and this might also be why, at least to my knowledge it’s only been legally reissued once circa 1990. A few months after hearing, another friend asked me if I thought the album was bad, and after some brief hemming and hawing I had to admit that I had no freaking idea. Asking me that question at that point in time was like asking me if Stan Kenton’s CITY OF GLASS or Miles Davis’s WE WANT MILES were bad. I mean “was” “it” “bad”? And “how” “why”, etfuckingcetera. Shit. I just wasn’t prepared to process something so far outside my interest in blues, trad rock, punk, and a smidgen of jazz. Now for the record, Kenton; no, Miles: yes, and TRANSLUCENCE: no. While Poly’s debut solo stab will likely never enter my steady listening diet, I feel secure in describing it as a largely successful (if occasionally problematic) and enjoyable statement of artistic development. I grabbed a download of it a few years ago and have spent some quality time coming to grips with its documentation of sincere difference. It’s curiously one of the few examples of a record where I prefer the presence of a lilting, airy flute (not my fave instrument) to saxophone motion, but that’s mainly due to some Late Night Talk Show/Saturday Night Live Band style soloing on “Sky Diver”, a brief misstep. The overall sound of TRANSLUCENCE has been called a predecessor to Everything But The Girl, and while I have hardly listened to EBTG, I’ll agree that’s extant. But the record seems perfectly well suited for playing at non-obtrusive volume while reclining on a sandy, sunny beach under an enormous umbrella, sipping something sweet and strong from a coconut cup while reading a battered copy of Peter Matthiessen’s FAR TORTUGA. At least to my ears, it’s far more in keeping with calm, casual absorption then assertive listening, and hell, under the spell of my hypothetical seaside scenario maybe that janky sax would go down nice and easy. Shiver me timbers. That my feelings regarding TRANSLUCENCE register as something less than my love of Poly’s punk-era self are no reason for concern. Frankly, the need for the evolution of artists to remain close to any one person or group’s set of expectations is a spurious one. If a performer betrays previous work in an attempt for money, fame or legitimacy, that’s obviously different (but not any particularly big crime, either). However, if the growth is natural, as is the case with Styrene, then it should be accepted and even encouraged. Not that her work, at least in my case, was ever that far afield. She always felt in touch with punk while often swimming in different, less disruptive waters.

As noted above, the reason for this text is a sad one. Poly Styrene is gone, stricken by breast cancer. First Ari Up and now Poly. No other way to describe it; a flat-out drag. These days it’s basically impossible to check into Pitchfork without getting the skinny on the latest achievements of a bevy of talented women unencumbered by the odious interference of male-centric attitudes: Cat Power, Vivian Girls, Joanna Newsom, Best Coast, MIA, Wild Flag, on and on. But it wasn’t always that way. Once upon a time smart rock women were notable exceptions in the stream of things, and I hope my thoughts here have accurately communicated that Poly Styrene was one of the greatest of those exceptions. There will certainly be an outpouring of repetition on blogs and elsewhere in enthusiastic tribute to her greatness, but this is a case where the echo chamber is welcome and deserved. Some things just can’t be overstated. In ending, while I just said that Poly Styrene is gone, this is of course true only physically. Maybe I state the obvious, but as long as people are pumping their fists to “Oh Bondage! Up Yours!”, having moments of self-realization through “Identity” or spending a tranquil hour on the couch with TRANSLUCENCE, our heroine is still here in spirit. So please do you, me, the disaffected masses and Poly a big solid. Plug in, turn up, and keep listening.