It’s creeping up on twenty years since I first heard the late Steve Lacy. I’d read about him in the context of the free jazz scene of the 1960s, learning that he was an early associate of Cecil Taylor, that he’d recorded an album on ESP Disk, that he’d moved to Paris in the late 60s and had continued to explore and grow musically, and that at that point (just after the dawn of the 1990s) he was still working and releasing records. By chance while record shopping, I found a then recent LP copy of The Door, released on RCA Novus, quickly bought it and wasn’t disappointed.

This was the beginning of my seduction by jazz, which coincided with a rekindling of interest by both record companies and a portion of the general public in less traditional modes of improvisation. Both Taylor and Sun Ra had new records out on A & M, Elektra was releasing the music of John Zorn and other New York Downtown artists on the Nonesuch imprint, Columbia had Tim Berne, a steady flow of indies (some with major label distribution) were releasing new jazz of an unabashed post-free stripe into the marketplace, and the availability of classic recordings on Impulse!, Atlantic, Blue Note, and Columbia made it possible to get frequent audible instruction into the huge and often uncompromising history of the music And Lacy threads through the post-50s portion of that history like a friendly but demanding snake.

This was the beginning of my seduction by jazz, which coincided with a rekindling of interest by both record companies and a portion of the general public in less traditional modes of improvisation. Both Taylor and Sun Ra had new records out on A & M, Elektra was releasing the music of John Zorn and other New York Downtown artists on the Nonesuch imprint, Columbia had Tim Berne, a steady flow of indies (some with major label distribution) were releasing new jazz of an unabashed post-free stripe into the marketplace, and the availability of classic recordings on Impulse!, Atlantic, Blue Note, and Columbia made it possible to get frequent audible instruction into the huge and often uncompromising history of the music And Lacy threads through the post-50s portion of that history like a friendly but demanding snake.

Before the internet, the most reliable way to learn about the movements, personalities, and recordings in jazz’s long and varied landscape was by reading books. Martin Williams, Nat Hentoff, and Gary Giddins became familiar, reliable names. It quickly became easy to distinguish the large number of conservative books and opinions from those that were more attuned to the sounds of freedom. The cornerstones of my jazz infatuation at that point consisted of two genres and two artists: Free jazz, Bop, John Coltrane, and Charles Mingus. I had no time for revamped moldy-fig bullshit or upscale cocktail self-congratulation: groundbreaking and demanding music was what I was after, and the texts that accepted or celebrated the more controversial aspects of jazz in its slow commercial decline were my guide in buying the documents that served as the building blocks in my jazz education.

Before the internet, the most reliable way to learn about the movements, personalities, and recordings in jazz’s long and varied landscape was by reading books. Martin Williams, Nat Hentoff, and Gary Giddins became familiar, reliable names. It quickly became easy to distinguish the large number of conservative books and opinions from those that were more attuned to the sounds of freedom. The cornerstones of my jazz infatuation at that point consisted of two genres and two artists: Free jazz, Bop, John Coltrane, and Charles Mingus. I had no time for revamped moldy-fig bullshit or upscale cocktail self-congratulation: groundbreaking and demanding music was what I was after, and the texts that accepted or celebrated the more controversial aspects of jazz in its slow commercial decline were my guide in buying the documents that served as the building blocks in my jazz education.The curious thing about Steve Lacy is that he was given an unusually high level of respect from the more stodgy historians and critics when they actually deigned to write about him. The less forgiving or antagonistic treatment leveled at names like Albert Ayler, Anthony Braxton, Sun Ra, and Archie Shepp was mostly absent from the writing on Lacy. A big reason for this is his unique background, playing progressive Dixieland before hooking up with Taylor on the pianist’s early recordings, joining arranger Gil Evans in the late 50s and playing with Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk, and serving as the inspiration for Coltrane to pick up the soprano sax. Lacy was an inside/outside cat, and while he gravitated more to the outside as the 60s progressed, he never really became a flat-out wailing wildman on his instrument. He did participate in some rather intense large group improv sessions (The Jazz Composers Orchestra and Globe Unity Orchestra spring to mind) but in the parts of the man’s massive discography that are completely (solo sax records) or largely (extensive duos, trios and quartets) his Lacy exudes a contemplative nature that stands in contrast to the modes of full-blown anger/protest or ecstatic abstract joy. His choice of instrument certainly plays a big part in this, as does his extensive examination of the music of Monk. To call him an avant-garde traditionalist might seem like a contradiction, but after hearing a wide variety of his work it sort of makes good sense.

The second Steve Lacy record I bought was Soprano Sax. This was his debut as a leader, and I ordered it on a whim, knowing little about its contents. I did know that it came after he joined Taylor’s group, but since finding early Taylor records was a struggle at that point, I only had the idea of what those early Cecil groups sounded like as a possible indicator of what might come from Lacy’s first album. Upon taking Soprano Sax home, quickly disposing of the plastic (this was a CD reissue) and digging in, it just as quickly became obvious that any hypothetical notions I’d formed about the music were off the mark: it was a completely inside record. The firmly traditional approach to the music was handled with an appealing amount of depth, and I found myself returning to the album quite frequently, it's contents helping to play a large part in expanding my horizons to the more classic sounds that weave back to the music’s origins.

The sound of the soprano sax is an odd one. Even when it’s being used to examine standards by Duke Ellington or Cole Porter, the shrill, nasally, occasionally harsh tone sits in stark distinction to the warmer, deeper sounds found in the more regularly employed altos, tenors, and baritones. There was a reason that the soprano was almost completely abandoned in the bop era, relegated to the purgatory of Dixieland’s collective boisterousness: it’s simply a harsh mistress (Lacy once described it as a hysterical woman) that’s less forgiving and more demanding than most people are comfortable with. So while Soprano Sax makes no overt gestures to being avant-garde or out-of-step with the times of its creation, the unique sound of the titular instrument helps it to achieve an immediate magnetism, which is only increased by the fluidity and daring of a player like Lacy.

Having a great band plays a big part in being able to reach such heights. Wynton Kelly on piano is a heavyweight addition, a nimble player that contributed to landmark recordings by Miles and Coltrane and also sounded great in his own trio (who happen to be the accompanying group on Wes Montgomery’s ludicrously wonderful Smokin’ at the Half Note). Kelly had a lot of worthwhile contemporaries, but in my opinion few of them could have contributed as strongly to this album as he does, shifting from the roles of support to soloist with easy grace and attractive assurance. Bassist Buell Neidlinger is probably an unknown name outside of serious jazz-heads, but that doesn’t mean he’s a footnote: he played an integral part of Lacy’s and Taylor’s music during this period, culminating in important sessions for the Candid label, one of which was originally released under his name as New York City R & B (with Lacy, Taylor, Shepp, Billy Higgins, Clark Terry and others). He’s worked with classical groups and been an LA session musician, and he was a vital component of the period where the free-jazz dial was set to simmer, not yet turned up to full boil. I think he was a great player. I feel the same way about Denis Charles, the drummer in this group, another lesser-known but worthy figure, who in addition to the Lacy/Taylor connections (he appears on the Candid sessions as well) also recorded with Sonny Rollins, violinist Billy Bang and free-bassist extraordinaire William Parker. He was a native of the Virgin Islands, and the playing I’ve heard from him is quite vibrant, particularly his cymbal work, where he genuinely expresses rhythm creatively instead of just falling back on standard clichés. Charles’ career featured some lengthy drop-outs and periods of little activity, which is unfortunate, for like Higgins and Ed Blackwell, he was versatile and expressive, capable of contributing in a variety of styles. More recordings of his prowess would certainly have helped to tip the scales of notoriety in his favor. But what we got is all we have, and this recording is one part of that total.

Having a great band plays a big part in being able to reach such heights. Wynton Kelly on piano is a heavyweight addition, a nimble player that contributed to landmark recordings by Miles and Coltrane and also sounded great in his own trio (who happen to be the accompanying group on Wes Montgomery’s ludicrously wonderful Smokin’ at the Half Note). Kelly had a lot of worthwhile contemporaries, but in my opinion few of them could have contributed as strongly to this album as he does, shifting from the roles of support to soloist with easy grace and attractive assurance. Bassist Buell Neidlinger is probably an unknown name outside of serious jazz-heads, but that doesn’t mean he’s a footnote: he played an integral part of Lacy’s and Taylor’s music during this period, culminating in important sessions for the Candid label, one of which was originally released under his name as New York City R & B (with Lacy, Taylor, Shepp, Billy Higgins, Clark Terry and others). He’s worked with classical groups and been an LA session musician, and he was a vital component of the period where the free-jazz dial was set to simmer, not yet turned up to full boil. I think he was a great player. I feel the same way about Denis Charles, the drummer in this group, another lesser-known but worthy figure, who in addition to the Lacy/Taylor connections (he appears on the Candid sessions as well) also recorded with Sonny Rollins, violinist Billy Bang and free-bassist extraordinaire William Parker. He was a native of the Virgin Islands, and the playing I’ve heard from him is quite vibrant, particularly his cymbal work, where he genuinely expresses rhythm creatively instead of just falling back on standard clichés. Charles’ career featured some lengthy drop-outs and periods of little activity, which is unfortunate, for like Higgins and Ed Blackwell, he was versatile and expressive, capable of contributing in a variety of styles. More recordings of his prowess would certainly have helped to tip the scales of notoriety in his favor. But what we got is all we have, and this recording is one part of that total.Soprano Sax starts with a reading of Ellington’s Day Dream, with Lacy’s tone cutting and sometimes soaring while retaining a lightness of delivery that’s quite pleasing. He becomes more forceful in his solo without becoming showy or blustery. On this track he’s above all else about restraint while keeping tabs on the inherent beauty of the tune, managing to express something of himself in the process. Kelly gets a turn to solo, and sounds fantastic. The next song, Alone Together is a standard, and it finds Lacy’s blowing ranging from knotty to searching, with an especially well done solo in between great showings by Neidlinger and Kelly. Charles hangs back, giving the tune much more than just a pulse. Monk’s Work is tackled next, and shows Lacy to be adept at maintaining momentum while playing imaginatively. Another fine Kelly solo gives way to a brief and energetic (to say nothing of unusual) one by Charles, and then Lacy returns for more expressive forward motion. It is at this point that the record really kicks into high gear. Ellington’s Rockin’ in Rhythm is given a work-out, with superb ascents and declines by the horn, thrilling contributions by Charles, who really knows how to adapt to and accentuate the songs form (fucking fantastic cymbals), and more solo space for bass and drums (Kelly really making the most of his spot). A calypso titled Little Girl Your Daddy is Calling You is next, and Lacy is for the most part absent, only playing on the opening and closing of the tune, laying back so his band mates can shine: Kelly tears it up, roaming over his keyboard with a delicious dexterity, at times pushing at the tune’s tempo and at other moments falling back, flurries of sound flirting around with melody then returning to runs of notes, before concluding and giving way to the drums, which rattle around in some weirdly compelling almost marching band territory (with some cool attention to the hi-hat) before the song’s sweetly abrupt end. The last track, Cole Porter’s Easy to Love, serves as both a stretching out and as a winding down. Lacy gets extended solo space that he utilizes quite well, never running out of interesting places to go. For me, the best part of the song is Neidlinger’s strong walking rhythmic line and his seamless transition into a fine solo spot. But the overall strength of the whole record is the ease of communication between all the players. Lacy, Neidlinger and Charles all knew each other from working with Taylor. I’m going to take a leap and say that Kelly and Lacy were familiars from the circles of Evans and Davis. This level of group knowledge obviously encourages the individual players to take subtle chances while recording, bolstering the confidence and helping the finished work to rise far above just another solid recording date. For Lacy’s Soprano Sax is so much more than a collection of fine players who happened to end up in a recording studio for pay. It is both a lasting document of the reintegration of a neglected instrument into the fabric of jazz, and the beginning of a startling career, one that never displayed signs of coasting or apathy. Whenever another Lacy recording enters my eardrums, I almost always end up pulling out this disc, partly for the sheer joy of it, but also to see how far the man traveled over the course of his life. And Soprano Sax never sounds dated or bland. It is a record of its time, certainly, but its approachable, trad quality doesn’t for a second feel like coasting or compromise. These four guys were working things out the way they wanted to, coming to terms with the history of this music not just as listeners (a big enough task), but as players. This is something that Lacy never stopped doing, no matter how abstract his later work became.

Thelonious Sphere Monk was a big part of this constant process. Lacy’s next record as a leader consisted entirely of Monk compositions. It was the first album to solely feature the pianist’s work in interpretation. Reflections: Steve Lacy Plays Thelonious Monk is a landmark record for so many more reasons than just that: it is the end-product of a stellar band of Lacy, Neidlinger, pianist Mal Waldron, and drummer Elvin Jones, it is a sincere and successful investigation into the work of one of the greatest musicians of the 20th century recorded at a time when the artist was still a contentious figure, not yet the canonical influence who has inspired far too many tributes (some of which reek of opportunism, others being wounded by an agape idolization), and it serves as evidence to just how diligent Lacy (and pianist Waldron, but more on him in a minute) was, so early in his career, at utilizing the substantial depths of Monk’s work (he did the same to a lesser extent with Ellington, Mingus, and pianist Herbie Nichols) as a basis for his own groundbreaking music. This is likely why he was treated so well in those jazz books: again, the hooks of the past are explicitly in Lacy’s oeuvre, even when he’s at his most out. But the focus is always on new possibilities. It’s a bit like watching somebody make an awesome sculpture out of old car parts. The end result is this unique and tangible thing comprised of elements that are unavoidably familiar (we’ve all taken a car apart before, right?). In comparison, the slavish tribute albums (not ALL of them are bad, but that’s another blog entry) feel like eating an attempted facsimile of a really good meal where the chef abstained from using spices and substituted sub-par produce for fresh, organic ingredients. Lacy's work is alive and bursting where the tribs are flaccid and lacking. Another striking thing about Reflections is how it avoided Monk standards in an era when there weren’t any. That means no Round Midnight or Straight No Chaser, but not in the deliberate way that the omission of those tunes can’t avoid today. Four in One jumps out of the gate with stirring group interplay, the tune’s title lending commentary to the collective artistry on display. The first striking difference between this group and the one on Soprano Sax is Waldron: Kelly is a more direct player, with an energetic style that made him well suited for the steady flow of post-bop recording that didn’t really abate until the later half of the ‘60s. Waldron is a more contemplative pianist, directly influenced by Monk, less melodic in his soloing, and finally someone who was inclined toward the more progressive developments in jazz. His imprint is on the Eric Dolphy-Booker Little Quartet’s Live at the Five Spot recordings, which is reason enough to enshrine him in the halls of jazz glory, but in addition to that he continued to be a thought provoking player up to the end of his life, often collaborating further with Lacy in a variety of contexts. In many ways he’s shares Lacy’s mode of continually moving forward by deeply looking backward, but Waldron’s less appropriately tagged as an avant-garde player. The avant influence, at least from his music that I’ve spent time with, is more implicitly felt than explicitly stated, but this internal openness gives his later work (again, what I’m familiar with. The man was quite prolific) a vitality that many other pianists with more rigid, codified styles simply lack in their own late works. Like Lacy, he was another European expat, and perhaps the respect and relative freedom of that locale helped him to retain the spark.

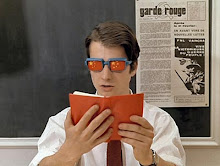

Lacy and Waldron in performance circa 1980

Another quickly apparent difference in the band is Elvin Jones. Most of his posthumous fame comes from his membership in Coltrane’s groundbreaking later bands, but equally important to a full understanding of his abilities is his sheer adaptability to whatever style he was involved in playing. The list of musicians he connected with is rather astounding: Davis, Lee Konitz, Art Pepper, Roland Kirk, Andrew Hill, Rollins, Wayne Shorter, Grant Green, Larry Young, Bill Frisell, etc. Jones could function admirably in numerous contexts while always bringing the necessary ingredient of individuality that marks the great jazz drummers. His playing is the first thing heard on Four in One, but it’s what he does during Lacy’s excellent solo that really stands out. While he is never out of the support role, there is a disciplined raucousness to his playing, which downshifts noticeably when Waldron takes the solo spot, Jones focusing instead on expressive cymbals, letting the piano dominate the moment. The subsequent back and forth between Neidlinger and Jones is loose and surprising, lacking the triteness that 50s rhythm sections could often fall into. Something I’ve noticed in Jones’ early work is how bursting with expression it is, tilting to the explosions that would come later with Coltrane, but also how he never overtakes the other players, overstepping into showiness. This record, along with Rollins’ Live at the Village Vanguard albums, prove just how developed an artist Jones was before joining Coltrane.The third noticeable difference between this record and Soprano Sax lies in Lacy’s playing. The challenge of seven Monk tunes possibly inspired him to a heightened level, for he sounds richer and displays more dexterity than on his debut, but the period of time between recording dates, nearly a year, is likely to have also played a part. Practice, performance, listening, and thinking (reacting) are all vital to a musician (you don’t have to be one to know this), and on Reflections Lacy is in exemplary form. On one hand, the playing seems more relaxed. But on the other, this relaxation also seems to bring more intensity to his sound through increased chance taking and the natural upper register timbers that his instrument possesses. What results is a beautiful glimpse of individual artistry. Lacy knew something fifty years ago that many don’t know or ignore today: that the true way to interact with the music of a master is to bring the idiosyncrasies of your own personality into the fray, and to have a discussion of sorts, instead of a monologue, an imitation.

The high points on this album are the opener discussed above, the infectious angularity of Bye-Ah, and the onslaught of thick communication and tense improv that is Skippy, the closing track. But that leaves four others that aren’t far behind. The whole thing is like a diamond tough testament to the greatness of Lacy, and it lumps together with Soprano Sax to shed lasting light on part of the early movements of one of music’s great improvisers.

Of all the players on both discs, only Neidlinger is still making music. All of the others have died, though the creative part of who they were continues to live through their recordings, and every time someone hears their music, either consciously or by chance, the opportunity for pleasure, for inspiration, for fulfillment (if only for a moment) is there. If the only real point to being alive is to live a life not wasted, then all these guys not only succeeded many times over, but they grabbed thousands of people by the ear canals and brought them along for the ride. How gracious.